How Do Family Caregivers Fare?

Number 3, June 2005

Visit profiles to view data profiles on chronic and disabling conditions and on young retirees and older workers.

A Closer Look at Their Experiences

Caregiving is often life changing and consuming, leaving some caregivers exhausted and depressed. Some 15 percent of family caregivers report high levels of overall stress as a result of caring for an older family member or friend with long-term care needs.(1) Caring for a friend or relative, however, can also be a positive and rewarding experience. Many caregivers handle the stress well by turning to friends and family or prayer to help cope.

This Profile provides an overview of the physical, emotional, financial and social experiences of primary family caregivers. Primary family caregivers are people who take responsibility for coordinating and providing the majority of the care received by someone who needs long-term care. Long-term care is the need for assistance performing one or more Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) such as doing housework, managing medication or finances, or transportation, and/or Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) such as eating, bathing, dressing, using the toilet, or moving about.

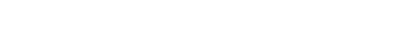

The majority of primary caregivers feeling stressed are women

The majority — 64 percent — of all primary family caregivers are women.(2) Roughly four out of five primary family caregiver who report that caregiving is stressful are women(3), and roughly three-quarters of primary caregivers who report feeling “very strained” physically, emotionally, or financially as a result of providing care are female (See Figure 1).

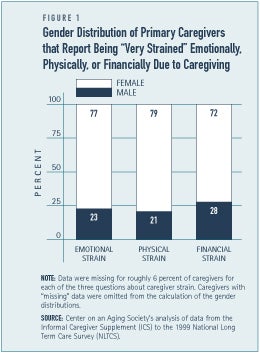

Caregiving often changes daily life

Being a primary caregiver is time-consuming. Nearly one in five primary caregivers — 19 percent — report that their relative or friend requires constant attention.(4) Caregiving often usurps the time available to spend with other family members or friends, and limits the time available to participate in other social activities, hobbies, community activities, regular exercise, or vacations. Nearly a third — 31 percent — of caregivers report having less free time or a limited social life due to caregiving (See Figure 2).

Providing care to a family member with long-term care needs often necessitates the transfer of personal information about the care recipient or the care provided, or the acceptance of “strangers” such as formal care providers into their home, resulting in a lack of privacy. Some 18 percent of caregivers feel that their privacy as been invaded (see Figure 2).

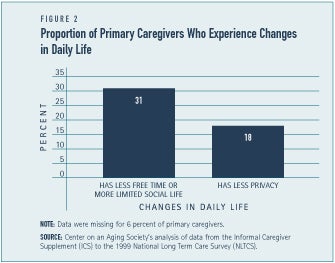

Some caregivers feel overwhelmed

Family caregivers often become caregivers with little or no preparation, support, or understanding about providing long-term care. The experience can be overwhelming. Over one-fifth — 22 percent — of caregivers are exhausted when they go to bed at night, and many feel that they cannot handle all of their caregiving responsibilities (see Figure 3). Some 13 percent of caregivers feel frustrated with the lack of progress made with the care recipient.

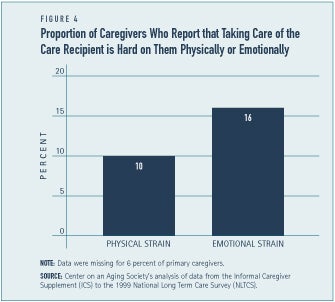

Emotional strain is more common than physical strain among primary caregivers

The physical stress of caregiving, especially in relation to providing care for someone who is bedridden or wheelchair bound, can affect the physical health of the caregiver. One-tenth of primary caregivers report that they are physically strained (See Figure 4). Similarly, about one in ten caregivers — 11 percent — report that caregiving has caused their physical health to get worse.(5) A decline in the physical capacity of caregivers affects their ability to continue providing care and increases the risk of their own frailty later in life.

The emotional strain of caregiving is somewhat more prevalent. Some 16 percent of caregivers feel emotionally strained (See Figure 4) and 26 percent say taking care of the care recipient is hard on them emotionally.(6) Caregivers often report feeling frustrated, angry, drained, guilty, or helpless as a result of providing care. Caregiving can also result in feeling a loss of self identity, lower levels of self esteem, depression, con-stant worry, or feelings of uncertainty.

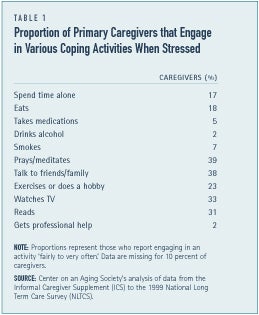

Caregivers generally cope well with their responsibilities

The majority of primary caregivers do not report feeling stressed. Although, many do engage in various activities to help them cope (see Table 1). Over one-third of caregivers turn to prayer or meditation. Nearly two out of five caregivers — 38 percent — report that they talk with family or friends when stressed. Relatively few caregivers report engaging in drinking or smoking explicitly to help them cope with their caregiving responsibilities.

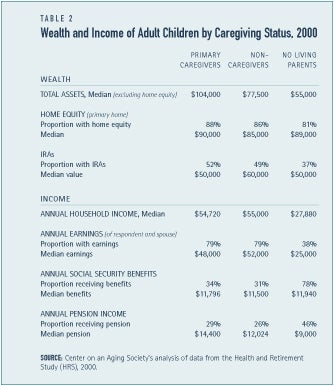

Caregivers are somewhat wealthier than non-caregivers

Although Medicare, Medicaid and pri-vate insurance represent the majority of long-term care expenses, much of the financial burden associated with long-term care weighs heavily on the pockets of care recipients and their family. The majority of caregivers — 60 percent, however, do not feel that caregiving causes any financial hardship.(7) One in ten caregivers reports that caregiving causes a fair amount of financial difficulties. Most primary caregivers, however, are not low-income and tend to have more wealth, on average, than non-caregivers (see Table 2). Low-income caregivers are more likely to experience financial burden as a result of providing long-term care to an older family member or friend than caregivers with higher incomes.

Caregiving can affect work, income and savings

Caregiving can interfere with work, causing the caregiver to take time off from work without pay, cut back on the number of hours worked per week, retire early, or leave the workforce entirely; all of which can affect a caregiver’s income and financial resources. Some 17 percent of caregivers worked fewer hours, 16 percent have taken time off without pay, and 8 percent quit their jobs to provide care.(8) In the long run, there could be considerable financial consequences to caregivers who reduce their hours or retire early as a result of their caregiving responsibilities, especially lower income caregivers.

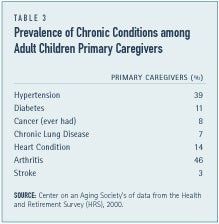

Chronic conditions are somewhat common among caregivers

Although the majority of caregivers are in good physical health, it is not uncommon for caregivers to also have chronic health conditions (see Table 3). Some of these conditions could interfere with the availability and ability of caregivers. For example, almost half — 46 percent — of caregivers suffer from arthritis, a chronic condition that can potentially cause severe physical limitations.

Caregiving can also be a rewarding experience

Although caregiving is a taxing experience, it also has positive and rewarding side-effects. For example, almost half — 47 percent — of caregivers strongly agree that they appreciate life more as a result of their caregiving experience.(9) A similar proportion — 48 percent — report that caregiving has made them feel good about themselves. Other studies have suggested that caregiving has lead caregivers to feel useful or proud, or experience personal growth or an enhanced relationship with the care recipient and other family members.(10).

Conclusion

The stress associated with providing care can be detrimental to the health and well-being of both the caregiver and the care recipient putting the care recipient at risk today and putting the caregiver at risk when they are older and frailer. While caregivers tend to cope well with the stressors of providing care, easy and affordable access to information, education, and training about long-term care as well as technology, support groups, counseling, respite care and financial assistance are beneficial to the well-being of both the caregiver and the care recipient.

1. Center on an Aging Society’s analysis of data from the Informal Caregiver Supplement (ICS) to the 1999 National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS). On a scale of 1 to 10, 10 being the highest level of stress, the term “high levels of overall stress” represents a rating of 6 or higher.

2. Mack, K., & Thompson, L. (2005). A Decade of Informal Caregiving: Are today’s caregivers different than informal caregivers a decade ago? Data Profile (Washington, DC: Center on an Aging Society), http://ihcrp.georgetown.edu/agingsociety/pubhtml/caregiver1/caregiver1.html.

3. Center on an Aging Society’s analysis of data from the Informal Caregiver Supplement (ICS) to the 1999 National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS). On a scale of 1 to 10, 10 being the highest level of stress, the term “stressful” represents a rating of 6 or higher.

4. Center on an Aging Society’s analysis of data from the Informal Caregiver Supplement (ICS) to the 1999 National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS).

10. Amirkhanyan, A.A., & Wolf, D.A. (2003). Caregiver Stress and Noncaregiver Stress: Exploring the Pathways of Psychiatric Morbidity. The Gerontologist 43(6):817-827.

ABOUT THE DATA

Unless otherwise noted, the data presented in this Profile are from the 1999 National Long Term Care Survey (NLTCS) and its Informal Caregivers SUpplement (ICS). Additionally, data from the 1989 and 1994 NLTCS and the ICS to the 1989 NLTCS, are presented to illustrate how informal caregiving has changed over the past decade. The NLTCS and the ICS are sponsored by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and conducted by the Center for Demographic Studies at Duke University. The National Long-Term Care Surveys are nationally-representative, household surveys of the population age 65 or older living in both the community and institutional settings. The Informal Caregiver Supplement to the NLTCS collects data on the experiences of the primary informal caregivers of the disabled population age 65 and older living in the community.

The ICS defines p[rimary caregivers as persons providing the most hours of unpaid assistance with either Activities of Daily Living (ADL) or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL).

ABOUT THE PROFILES

This is the first in a set of Data Profiles, Family Caregivers of Older Persons. The series is supported by a grant from AARP and MatherLifeWays. This Profile was written by Katherine Mack and Lee Thompson with assistance from Robert Friedland.

The Center on an Aging Society is a Washington-based nonpartisan policy group located at Georgetown University’s Institute for Health Care Research and Policy. The Center studies the impact of demographic changes on public and private institutions and on the economic and health security of families and people of all ages.